Questioning Genome Studies and Bioessentialist Psychiatry

Notes + Readings from E03: Genome Wide, Ass Studies

“A simplistic biological reductionism has increasingly ruled the psychiatric roost... [we have] learned to attribute mental illness to faulty brain chemistry, defects of dopamine, or a shortage of serotonin. It is biobabble as deeply misleading and unscientific as the psychobabble it replaced.”

- Andrew Skull, Professor of History of Psychiatry, Princeton University, in the Lancet

TLDR;

In EP 03, we question the newest flavor of bioessentialist research that aims to prove “genetic mutations” are the cause of mental illness — genome wide association studies. These studies, spurred by funding from the US and UK governments, have grown immensely popular and taken on a significant amount of cultural currency in a capitalist society that worships data.

We also discuss how race science is still a dominant norm in medicine, with researchers framing race as a biological category while studying disease without considering social context, and why this bogus research is championed by alt-right, milk-chugging, neo-nazis.

Bioessentialism — the belief that our biology determines who we are without any consideration of context or environment — is not new in scientific research.

Across history, people in power have justified oppressive social constructs by using flawed research to argue that things like race, gender, sex, and madness are biological differences that separate humans into distinct, hierarchical categories.

In this episode, we challenge the idea that science is apolitical and question the illusion of objectivity, arguing that science under capitalism is shaped by oppressive norms and often produces inaccurate, biased conclusions that are exploited to strengthen power structures.

Still Can’t Find Those Biomarkers!

Researchers have been hunting for them for decades, but there still aren’t any biomarkers like genes, brain structures, or pathogens reliable enough to use for diagnosing psychiatric disorders.

The DSM and the ICD lack scientific validity — meaning, there’s no consistent, reproducible evidence that the behaviors and traits we call mental disorders are caused by biological pathologies. This doesn’t mean they aren’t real experiences that people have, just that there isn’t scientific evidence that they are the result of chemical imbalances or gene mutations like we are often told.

It’s more complicated than that, but reducing complex human experiences to simple cause-and-effect with easy, marketable solutions is the most profitable, so these ideas tend to thrive.

DSM diagnoses weren’t created through research, but by small committees of professionals voting on them — it’s a subjective list of criteria that pathologizes people’s deviant traits and stress responses without considering the effects of struggling to survive in an oppressive society.

Studies that claim to show there are unique biomarkers or neuroanatomical signatures for psychiatric disorders often do not account for confounding variables like the effects of long-term medication or are, to quote a critical review, “short on methodological rigor”.

From Phrenology to Neuroimaging to Genomes

Computing power has made it possible to reduce humanity down to data, something researchers have been trying to do since eugenicists measured skulls to claim that racism was scientific.

Now, we have fMRIs, but neuroimaging studies on human behavior have been called “neophrenology” — a modern method of biological comparison used to make reductive arguments about humanity.

Brain imaging has been shown to make an argument more believable, even if it isn’t logically sound. For example, numerous papers claimed to have found the “dysfunction” of ADHD in the frontal networks by comparing the size of various brain areas to “healthy” controls. They argue that because they’ve found some ADHDers have reduced grey matter or smaller cerebellums, this is a neuroanatomical signature of ADHD.

However, these kinds of studies have been criticized for having serious flaws in study design and methodology that invalidate their conclusions. A 2018 review by Marley et al found that neurobiological research into ADHD, for instance, hasn’t advanced since a critical review in 2003 found similar methodological problems.

Here’s a few of the major criticisms from these reviews:

Because neuroimaging is extremely expensive, most of these studies have very small sample sizes (<15 patients) which can’t be generalized to entire populations. This means that data is being molded to yield desired results.

Study participants in the diagnosed group are often on long-term psychiatric medications relative to the unmedicated control group, which means any alterations in the brain could be due to the medications as opposed to an existing pathology. This is a confounding factor that makes it impossible to say whether a difference is innate or not.

The differences found in these studies are extremely small and inconsistent. (For example: a study from this year with a much larger sample size than usual found very little differences in brain structure between ADHD and non-ADHD subjects, counteracting many previous smaller studies that showed larger differences.)

Some of these studies do not control for confounding variables like age or size differences when studying children. Studies on ADHD or Autism-diagnosed children reporting reduction in brain volume sometimes have age gaps greater than 10 years between experimental and control groups, which means neurodevelopmental variation due to age is not accounted for.

And of course, things like socioeconomic status, poverty, and adverse childhood events are rarely accounted for.

Genome-wide association studies share similar problems to neuroimaging studies, like not accounting for confounding variables, but the fact that they utilize massive datasets appears to make them more robust.

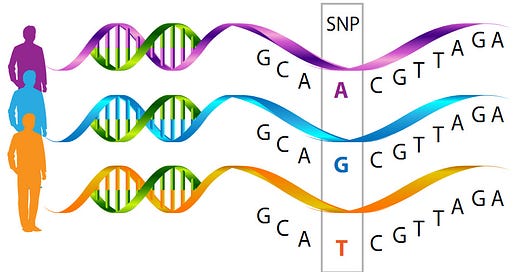

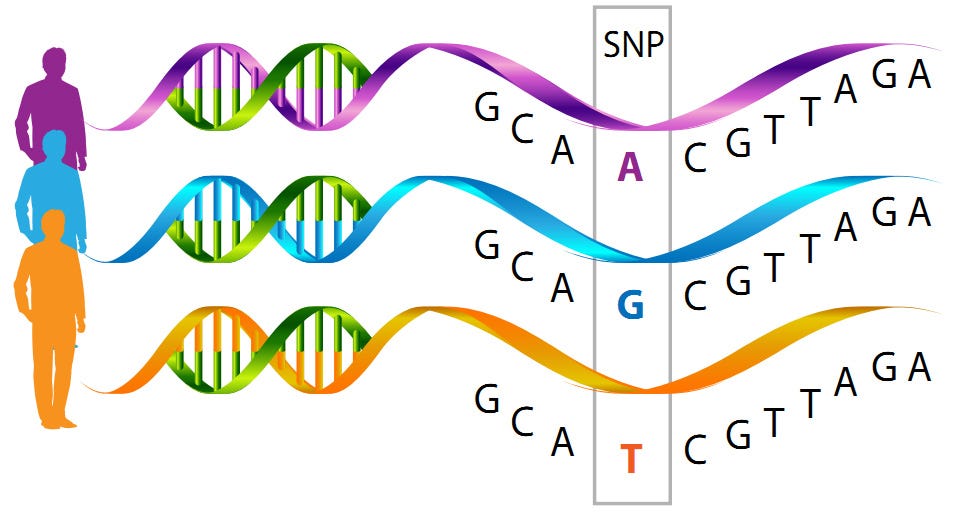

These kinds of studies scan tens of thousands of human genomes to find “genetic mutations” that are more often found in a “disease group” compared to a control group. This was made possible on a large scale by the Human Genome Project, which gave us new genome-sequencing technologies that can “read” the alphabets that make up human genomes and compare single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) between people.

The idea is that if genetic disease markers are found, they can be used to more accurately detect, diagnose, and treat people — something critical autism scholar Alicia A. Broderick has called the “cultural logic of intervention”.

Here’s a graphic that shows what GWAS studies try to do — find SNPs that show up more often in people diagnosed with “X disease” than those undiagnosed. Except, correlation is not causation, and people are a lot more complicated than yes disease/no disease.

What about other variables that influence the “disease” group? What about other factors they might have in common, like environmental stressors, socioeconomic status, lack of access to resources, exposure to state violence, marginalized identities?

GWAS don’t account for this. Let’s say, by chance, more individuals diagnosed with “X disease” love the color purple or have genes for Black hair compared to the control group. Does that mean those things cause the disease?

Of course not, but that is the underlying reductive assumption GWAS make. Since so many associations pop up (by chance), they have to pick which ones make sense. Often most don’t, but the SNPs that show up in genes related to brain function are arbitrarily chosen as relevant.

GWAS Case Study: A “Landmark” Schizophrenia Finding?

The first study we discuss claims to have found genetic variants implicated in schizophrenia:

A group of hundreds of researchers across 45 countries analysed DNA from 76,755 people with schizophrenia and 243,649 without it to better understand the genes and biological processes underpinning the condition. The new study found a much larger number of genetic links to schizophrenia than ever before, in 287 different regions of the genome, the human body's DNA blueprint.

The study was conducted by the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium, a group that includes over 800 researchers across the world who study “ADHD, Alzheimer’s disease, autism, bipolar disorder, eating disorders, major depressive disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder/Tourette syndrome, post-traumatic stress disorder, schizophrenia, substance use disorders, and all other anxiety disorders” which they openly admit are “syndromes that lack pathological or biological defining features”.

In the largest genome-wide association study to date, the research team identified a “substantial increase” in the number of genomic regions associated with schizophrenia. Within these regions, they then used advanced methods to identify 120 genes likely to contribute to the disorder.

Studies that use large datasets are seen as more credible, but in fact, issues with methodology are magnified with bigger numbers, further decreasing the validity of any conclusions.

If you don’t ask a very specific, precise question and normalize for all relevant confounding variables, then with big datasets, you will see some statistically significant variation between two groups purely by chance.

For example, if you take 50,000 random subjects and compare to 50,000 control subjects, you will find some “significant” differences, but that doesn’t make them valid or meaningful. Researcher Irving Kirsch uses this example:

Imagine that a study has been conducted on 500,000 people and has found that smiling increases life expectancy. This seems very impressive, but on reading further you discover that it increases life expectancy by only ten seconds. With 500,000 subjects, the effect is likely to be statistically significant, but it is not clinically meaningful.

The precise nature of the question you’re asking is important. In this study, they look at the genomes of ~325,000 people from diverse backgrounds and social contexts and lump them together to ask “do people with a schizophrenia diagnosis have distinct genome signatures?”

There’s no accounting for the social and environmental factors that could be distinct to the schizophrenia group, things like poverty and class, marginalization, and geographic region.

The experimental group could have lower income status and/or more exposure to systemic oppression and state violence, which could be explored for their association with schizophrenia, but they ignore all social variables that affect genomes and shape the experience we call schizophrenia. Instead, this study suggests a simple, causal relationship between a set of genes and a subjective diagnosis, treating the genome like a static code that “wires” us.

When Ass Studies Become Memes

The meme above refers (almost verbatim) to the title of a study that claims to have found "the first genome-wide significant risk loci for ADHD”.

This is an important illustration of how science jargon is used to relay unsupported, inaccurate conclusions as objective facts. Most often, the general public relies on the media to learn about research, and this is where a lot is lost in translation.

Just like other GWAS studies, this one ignores the impact of all socioeconomic and environmental variables, focusing on genes that impact brain function and finding scores of associations that still tell us nothing about causation.

A more recent ADHD GWAS study from February of this year states:

We found ADHD to be highly polygenic, with around seven thousand variants explaining 90% of the SNP heritability. Bivariate gaussian mixture modeling estimated that more than 90% of ADHD influencing variants are shared with other psychiatric disorders (autism, schizophrenia and depression) and phenotypes (e.g. educational attainment) when both concordant and discordant variants are considered.

The same genomic loci pop up in many studies in association with many psychiatric disorders. As the ADHD study admits, 90% of their loci overlap with other disorders, which invalidates the idea that they are uniquely associated with or directly cause ADHD. If they show up in multiple disorders and in different contexts, then that means the approach and methodology are wrong.

It’s also interesting to note that members of the Psychiatric Genome Consortium were involved in both these ADHD gene studies, which shows how a small group of researchers who receive government and corporate funding are doing much of this work. (For example: Benjamin M. Neale, who co-chairs the PGC’s ADHD workgroup and also contributed to this bipolar gene study that came out a few months later, is listed in the conflict of interest section as a consultant for three biotech companies.)

Capitalism Skews Scientific Research

Profit motive and careerism affect how science is conducted and what messages are communicated to the public. A paper titled “Messaging in Biological Psychiatry: Misrepresentations, Their Causes, and Potential Consequences” summarizes key issues in research and reporting:

…biomedical observations are often misrepresented in the scientific literature through various forms of data embellishment, publication biases favoring initial and positive studies, improper interpretations, and exaggerated conclusions.

These misrepresentations also affect biological psychiatry and are spread through mass media documents. Exacerbated competition, hyperspecialization, and the need to obtain funding for research projects might drive scientists to misrepresent their findings.

Moreover, journalists are unaware that initial studies, even when positive and promising, are inherently uncertain. Journalists preferentially cover them and almost never inform the public when those studies are disconfirmed by subsequent research.

This explains why reductionist theories about mental health often persist in mass media even though the scientific claims that have been put forward to support them have long been contradicted. These misrepresentations affect the care of patients.

P-Hacking Flawed Questions

Science is not apolitical or ‘objective’ — cultural biases shape how a study is designed, what research is funded, who gets funding, who is conducting research, and what questions they’re asking.

A p-value is a statistical threshold used to determine the probability that an association or pattern means something more than just chance. P-value hacking is a form of data manipulation that attempts to present certain patterns as statistically significant, when in reality, there is no underlying effect.

GWAS studies are particularly prone to this kind of data butchery because the threshold for what is considered significant is arbitrarily set, and bigger datasets magnify random associations when overly reductive, bioessentialist questions are being asked.

‘Do X genes cause Y mental disorder?’ is a fundamentally flawed question because it tries to study a condition as though it is an isolated system that is not influenced by any other variables from the environment.

People don’t exist in a vacuum. We exist in a complex web of interconnected relationships with people and non-human entities, systems we have to interact with, state control we are subjected to and capitalism we are forced to endure, along with other power structures that stretch across time.

P-hacking is incentivized in research because positive results that prove a scientists’ hypothesis lead to high-profile publications and more funding.

What is positive publication bias?

When the core motivation driving research is money, this affects the integrity of the science itself. Around 86% of publications yield ‘positive’ results, meaning they reinforce the researchers’ initial hypotheses.

Psychiatry and psychology have the highest positive publication bias of all medical fields. Popular journals prefer to publish “hot” results, while negative results that disprove the researchers’ hypotheses (such as studies that show psychiatric diagnoses are not rooted in biological abnormalities) are either ignored by the media or not published at all.

This means the studies that most people hear about are new, positive findings that haven’t been replicated (and often never are). Clinical trials reporting the beneficial effect of a medication are also more often published than those reporting no effect, and studies about psychotropic drugs are not immune to this publication bias.

These popular studies increase institutional revenue and are often funded by pharmaceutical corporations, which pay researchers well and help them further their careers. It is extremely difficult to obtain scientific recognition as a researcher without falling prey to these systemic problems.

The media also sensationalizes research conclusions, because emotionally triggering headlines get websites more clicks, which leads to more ad revenue. They often don’t report that study conclusions are uncertain, or discuss the study’s key limitations or design flaws; many articles tend to present studies in definitive ways that make the conclusions of one study on a small sample of people look like laws of nature.

Big Picture Question:

What’s the most obvious way that people in power can continue to operate oppressive, hierarchical systems with impunity?

By coercing and conditioning people to blame social problems on innate defects in some disordered individuals instead of seeing them as an outcome of a fundamentally violent, exploitative, inequitable society.

In order to maintain power and justify hierarchies based on social constructs like race, gender, and sanity, the 1% need the 99% to believe that these oppressive norms are rooted in biological differences.

The result of colonial, capitalist, western psychiatry is that individuals are blamed for their mental distress and treated with psychiatric medications or carceral approaches like institutionalization, approaches that exacerbate suffering without trying to address the oppressive social and economic systems that cause suffering in the first place.

A few more critical takes:

“New Concerns Raised Over Value of Genome-Wide Disease Studies”, Nature

“Why Biology Is Not Destiny”, The New York Review

“We Need To Throw Out a Mindblowing Amount of Science and Start Again”, The Spinoff